Table of Contents

- So this begs the question, what does the research say about both exclusionary and non-exclusionary timeouts?

- Timeouts and attachment theory

- Based on the evidence what’s the best approach to time-ins vs. timeouts?

- Time-in vs. timeout and the application of these questions

- Using the Magic of Redirection as an Alternative to Time-Ins and Time-Outs

- A final note on time-ins and timeouts

Pop psychology is littered with information on the consequences of timeouts and why parents should use time-ins instead. The truth is, it isn’t as cut and dry as that. Inside you will find info on positive discipline including time-ins as well as what research says about both disciplinary techniques.

The research on time-ins vs. timeouts isn’t clear cut. As an advocate for positive parenting, I have regularly written about how parents should not isolate their children when they are having a hard time.

And though I maintain this stance, it turns out, as is the case with many facets of life, the case against timeouts isn’t as clear-cut as that.

Consider the example of my son.

When life gets the best of my normally agreeable son, he can get emotional, irrational, and angry. When he’s like this, I can’t coach him through what he’s feeling.

This is how it unravels…

My daughter is playing quietly when my son interrupts.

Frustrated, she asks for space. My boy gets closer. I intervene by getting down to his level and reiterating his sister wants space. Then, I attempt to redirect his energy by suggesting we play together.

That’s when he responds with a primal grunt and get closer again. I give him a warning and tell him if he can’t respect his sister’s wishes, I will take him to his room.

He screams and knocks over her toys.

Then, I bring him to his room and try to stay with him.

I try to stay with my son because of all of the articles on time-ins vs. timeouts

The internet is peppered with articles questioning the efficacy of timeouts and suggesting the positive alternative of taking the timeout together.

This begs the question, what are time-ins?

Simply put, time-ins are inclusionary timeouts. The parent or caregiver removes a child from a situation to stop their misbehaviour. In contrast to timeouts, during time-in discipline, the parent stays with the child until he or she is calm.

Because this resonates with me, I did my best to be there for my little guy. No matter how hard I tried, all it did was escalate the situation.

Interestingly, the research on the effectiveness of time-in discipline is inconclusive.

As one researcher, George Holdon shared with Time Magazine:

“We’re currently doing research on whether time-ins work, but to my knowledge, there’s virtually no evidence on whether time-ins are effective,”

He furthers this by saying, “I think that’s going overboard [by forgoing time-outs]… There’s certainly a fair amount of research literature that shows time-outs can be effective in changing problem behavior.”

But it’s not just Holdon, Pediatric psychologist Amy Draton echoes this, stating we should not abandon an effective disciplinary practice in favour of one without evidence (3).

In addition, during my time writing this blog, I have been able to find research to support the claims by Holdon and Draton, but have yet to find evidence in support of time-ins.

It appears that the evidence in support of time-ins is anecdotal at best.

Read: Calm Down Corner: Why have one and what’s in ours

So this begs the question, what does the research say about both exclusionary and non-exclusionary timeouts?

The commonly used disciplinary technique in the US is timeouts, second only to discussions about a child’s behaviour (1). Despite their popularity, parents and caregivers largely misuse and misimplement timeouts.

Research from the beginning of the 20th century favoured more positive measures of discipline.

When timeouts emerged, they were intended as the last step in a series of disciplinary measures – not a stand-alone technique.

Research from the ’30s and ’40s suggested that caregivers should focus mainly on positive reinforcement. This meant that teachers and parents should largely focus on warm regard, positive reinforcement, modelling (2) and quality time together to facilitate good behaviour (1). This research suggested that effective discipline was contingent on positive reinforcers. Namely, children behaved their best when they had quality time with their parents, received praise, and parents used positive dialogue. This research also found that if positive measures weren’t met, children would likely be ambivalent if put in timeout (2).

When positive strategies didn’t work, then it is recommended that adults use a non-exclusionary timeout. This is where the child sits to the side with or without the adult. For instance, a teacher or parent who moves a child away from his peers and closer to the adult is performing a non-exclusionary timeout. Adults were only to use exclusionary timeouts in severe situations such as acts of aggression or with children who could not sit calmly to the side of a social situation. The main goal of timeouts was to temporarily remove the child from positive reinforcers for misbehaviour but not break the attachment bond.

Timeouts and attachment theory

Secure attachment is critical for a child’s wellness.

A secure attachment bond ensures that your child will feel secure, understood, and calm enough to experience optimal development of his or her nervous system. Your child’s developing brain organizes itself to provide your child with the best foundation for life: a feeling of safety that results in eagerness to learn, healthy self-awareness, trust, and empathy.

Jeanne Seagle, Ph.D.

Because of this perspective, many experts recommend time-ins so as to not break or damage the attachment bond. They fear timeouts may communicate to the child, “I am not there for you when you are struggling the most.” As previously stated, the limited research on time-ins shows no evidence they are effective. In addition, secure attachment isn’t jeopardized by temporarily separating from a child (1). In fact, research shows that timeouts can, in fact, be effective. For instance, they offer the child and parent the opportunity to calm down. As such, researchers Dadds and Tully suggest reassuring children when separating from them for disciplinary purposes. For instance, say: “You are loved, you are my child, you are safe, this is not about you or us, it is just about this instance of aggression (1).

Additionally, calm instructions before and calm directions after timeout actually promote emotional regulation (1).

Based on the evidence what’s the best approach to time-ins vs. timeouts?

First of all, the research suggests that when determining an effective disciplinary strategy for their own children, caregivers should ask themselves:

- Does the disciplinary measure deescalate the situation or increase a cycle of escalation? (In the case of my daughter, time-ins de-escalate and, in the case of my son, they escalate the situation.)

- Is discipline brief, calm and model functional coping strategies?

- Is the discipline strategy predictable and consistent for the child? And, does the parent feel calm and in control? Inconsistent, unpredictable discipline is related to an increased incidence of mental health issues in children (1).

- Does the parent intend to stop a behaviour that’s within the child’s control? For example, if the child is acting out of fatigue, overstimulation, or hunger? Am I expecting my child to behave in a way that is beyond her developmental ability? If so, a measure other than time-in or timeout is needed.

Time-in vs. timeout and the application of these questions

In our own home, basic needs such as connection, hunger, fatigue and overstimulation are often the reason my children struggle to behave. Because of this, my first step in discipline is to answer and potentially solve question 4. From there, if needed, I redirect their behaviour. For instance, if they have been rude or overly emotional, I offer a more functional way of conveying the same message. Or, if the kids are fighting, then I help script conflict resolution.

It is only when someone is unwilling to engage in conflict resolution or appropriate behaviour, I choose between a time-in or timeout based on what my kids respond to best.

Regardless of each kid’s preference, I don’t isolate a child who wants my support or is in distress.

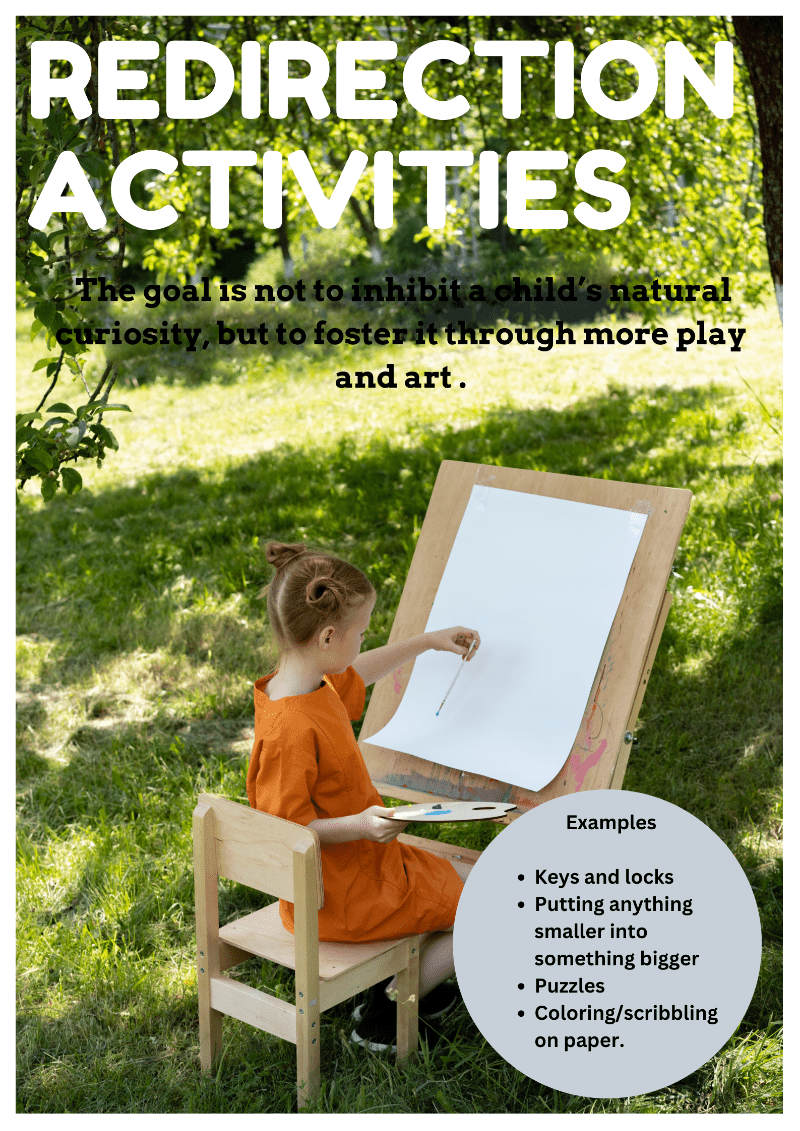

Using the Magic of Redirection as an Alternative to Time-Ins and Time-Outs

Redirection is a powerful parenting tool, especially when managing challenging behavior in children. So, what exactly is it? At its core, it involves skillfully steering your child’s focus from undesirable actions to more constructive alternatives. It recognizes that kids are naturally curious and impulsive, and it’s our role as parents to guide them gently and positively.

It’s best to stay vigilant and proactive when implementing redirection. When your child is in a stressful situation or grapples with big feelings that lead to impulsive or bad behavior, you need to step in calmly. Then, offer a different activity or interest that captures their attention and aligns with their age and development.

How to Redirect Effectively

The art of redirection lies in maintaining a warm and encouraging tone throughout – ensuring your child doesn’t feel like they’ve done something wrong.

For Older Kids

If an older child struggles to follow directions, offer them a fun challenge that involves following instructions, making it a game rather than a chore.

For Your Little Ones

When a young child is having a meltdown and feeling bad, try a co-regulation technique like a gentle hug or deep breathing exercises to help them regain impulse control and make a good choice in managing their emotions.

Remember, the key to redirection is consistency and patience. It’s about fostering your child’s ability to self-regulate, make good choices, and maintain a strong parent-child relationship, all in just a few minutes.

A final note on time-ins and timeouts

As of right now, research favours timeouts instead of time-ins. Based on this, if this form of discipline works and de-escalates the situation in your home, you may want to continue to use them. However, a child who is sad or desperate for a parent’s help should never be isolated. As is the case with all discipline, the main focus of any disciplinary measure should be on the child’s emotional and physical well-being as well as the ability to promote cooperation and better behaviour overall.

Like this post? Click on the image below to pin it for later!

Related reading on positive discipline

How to execute positive parenting from a position of strength

Science says this is how to execute discipline effectively

Scolding undermines effective parenting. This is why.

Parenting a strong-willed child? Here are 10 surefire tips.

What is positive discipline and why you might have it wrong

This is the crucial difference between positive and permissive parenting

Oh my gosh, I am on the verge of tears. I sent my son to time out yesterday. It makes me feel so bad every time I put him in time out. This article really helped me open my eyes and really think about what it means. Thank you. Very well written!

I am divorced and dont work. I am struggling with a 28 month daughter who wants to do everything alone whether she can or not and only when she wants.

When i tell her to do sth she rebels. Today she told me go away because i wanted to wipe her behind after making poop in the toilet. I tried to explain that she is still little to do so alone and it ended up in my struggling to wipe her and she screaming. This situation started this last few days. At noon she doesnt want to sleep although she still needs an one hour nap. At 17:00 then she wants to sleep.Moreover she doesnt want to play by her own. She wants me with ger all the time.

I put her on a time out for disobeying sometimes,not often.

Can you or sb else advise me on how to deal with the situation? How should i respond in every case?

Tnx a lot

Rosa Anigres

Rosa, it sounds like your daughter needs more control in her life. She needs to be offered choices all through the day. Also, read Whole Brain Child. Great way to rethink discipline.

Thank you for this. My 2.5 yr old son does the same when he is upset aksing for me, but then pushing me away. I wonder if you have any advice for sleep battles? My son wakes up in the middle of the night and tantrums (screams, hits, bangs on the wall etc.) unless we stay with him until he falls asleep. We go up when he wakes up upset and calm him down but then can’t leave his room or there will be a tantrum…. Do you have any advice?

What do you do if you have two (or more kids) who need Time Ins at the same time and won’t do well having the Time In together?